We are continuing in our series discussing Kids & Technology. In our last post, we looked at two approaches to parenting, generally-speaking, and how these can be instructive for how we approach technology with our children. In this post, we’ll learn about two key principles of technology from the field of media ecology, which will help us to understand the importance of intentionality when parenting our children in their use of technology.

In Psalm 115 we read…

2 Why should the nations say,

"Where is their God?"

3 Our God is in the heavens;

he does all that he pleases.

4 Their idols are silver and gold...

the work of human hands…

8 Those who make them become like them;

so do all who trust in them. (Psalm 115:2–4,8)

It is easy in our understanding of texts like this to think of idols in the spiritual sense, while losing the simple fact that idols are things crafted with human hands. They are tools. They have a connection to the spiritual, for sure, but are still, in their essence, merely objects made by human hands.

Did you catch what Scripture says about these idols? These inanimate objects actually shape those that make them, and even those that trust in them.

These things created by human hands are shaped by their creators, yet simultaneously, these things created by humans hands shape their creators as well.

As we think about idols, I think we tend to under-materialize the works of human hands in Scripture, but then we under-spiritualize the works of human hands today.

Philosopher Hannah Arendt put it this way…“…the things that owe their existence exclusively to men nevertheless constantly condition their human makers.” (Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition)

We make our tools, and our tools make us.

But how is it that our tools shape us?

We already have said in a previous post that every technology is an extension, but with every extension there is also amputation.

As we depend on technology for something, we then get worse at doing that thing, because we no longer have to.

Andy Crouch says that there are two promises with every technology: “Now you can” and “now you no longer have to.” But he says there are also two consequences with every technology: “Now you’ll no longer be able to” and “Now you’ll have to.”

In his 1964 book, the Technological Society, priest and philosopher Jacques Ellul warns, “The machine tends not only to create a new human environment, but also to modify man's very essence. He must adapt himself, as though the world were new, to a universe for which he was not created.” (Jacques Ellul, The Technological Society)

Millenia ago Socrates bemoaned the “amputations” that writing would have on the a person’s memory. He laments, “For this invention will produce forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it, because they will not practice their memory. Their trust in writing, produced by external characters which are no part of themselves, will discourage the use of their own memory within them.” (Socrates as quoted by Plato in Phaedrus)

To extend Socrates' groanings to a current technology, what consequences (a la Crouch) come of Google search? Well, to twin consequences: now you’ll no longer be able to remember any facts, or quotes, or…Bible verses, and now you’ll have to have a device on you at all times to access any type of important knowledge.

With every technology there is an extension, but there is also an amputation.

That’s the main thrust of Psalm 115:8; if we depend on an idol (extension) we no longer depend on the LORD (amputation).

Those who make them become like them;

so do all who trust in them. (Psalm 115:2–8)

Technology Is Not Neutral

Saying technology is not neutral is not a statement on its morality. It is not saying a piece of technology is morally good or morally evil.

To say technology is not neutral is to say that every technology has a bias. It has a telos or an end. Every technology is created with a purpose to achieve a certain job.

For us, as Christians, this principle squares nicely with our worldview.

We serve a God who creates with purpose, with intentionality. He created all things with a telos. As his image-bearers, we too create things with a purpose, with a telos.

Because every technology is created with a telos, every technology has an inherent bias, a way or purpose for being used. It has an bias baked into its very essence.

A pencil is created for writing.

A hammer is created for hitting.

A chair is created for sitting.

Because a technology has a bias does not mean that it can only be used in a certain way, but rather that the path of least resistance is that it be used in accordance with its bias.

That’s why it’s easier to use a pencil for writing than for roasting marshmallows.

Or it’s easier to use a hammer for hitting a nail than raking leaves.

In his book, Media Ecology, Lance Strate writes…

A bias does not represent absolute command over us…but rather a path of least resistance. We can always choose to move against the pull of the prevailing bias, and there is also the possibility of reinvention, as an alternate use of a technology that in effect transforms it into a different technology. The concern…is the degree to which we cede control to the biases of technology. (Lance Strate, Media Ecology)

We need to know and understand that each technology imbibes the intent of the creator, but also that it can morph into beyond the creator’s original intent (sounds a little like the story of Genesis 1–3). Again this does not communicate morality, but merely an operational bias.

This idea is so important for us as Christians to know and understand because it helps us to understand that technologies created by man do not always take us or our kids, or our society, or our churches down the same path that God wants us to go.

Especially in a culture shaped and animated by the Myth of Human Progress, we need to know and understand that our technologies are created by fallible people, and as such they often have fallible biases.

Oftentimes, we approach our technology like we’re getting on a bicycle; if we sit on a bike, it will only start moving if we pedal it, and will only go a direction if we steer it. It’s all about how we use it. The aims of the technology is dictated by the user, not the technology.

But that’s not how technology—especially those built around the foundation of the attention economy—operates. A much more apt metaphor for technology is like getting in a car and it idling forward. And really at the rate of technological change of today, it’s probably better said that using technology is like getting in an idling car that’s at the top of Pike’s Peak. If you don’t hit the brake, it’s just going to go barreling in one direction, and maybe a direction you don’t want it to go.

Not too long ago, I was eating breakfast with my boys, and my oldest son started to tell me something that happened during his rest time. “Dad,” he sheepishly began, “something bad happened during rest yesterday, and I need to tell you about it.”

Knowing what was coming because of my wife’s forewarning, I invited him to go on.

“The other day during rest, I asked Alexa to play Pete the Cat and a different song came on. And the girl said, ‘Oh. My. God, Becky. Look at her butt, it is so big.’”

Like a witness of a crime, my son’s face was concerned with what had transpired.

“That was bad,” he concluded.

I calmly said, “Ya, bud, that’s not good.”

My middle son, who is three and tends to be aloof in general, said, “What did she say?”

At which point my oldest son recounted it all over again.

So, we didn’t get into the objectification of woman, but did have discuss that those aren’t some of the words that our family says.

Now, that’s a silly example, and by God’s grace, a fairly inconsequential technological mishap. But it is illustrative of the fact that the desire we have to cultivate environments for our little plants to flourish in Christ is often overridden by the ends of a technocratic society.

These two principles—our technology shapes us and our technology is not neutral—will help us to be able to more fully understand our next post where we unpack the question: what our digital technologies are doing to our kids?

What are digital technologies doing to our kids?

You have undoubtedly heard it said that “Time is Money.” And it is true for tech companies, for social media juggernauts, for content producers. In the attention economy of today, in a world where Google’s ad revenue for 2022 (one year) was $224 Billion. Time is money.

But, I think the much more important idea for our conversation is the reality that time is formation.

Let’s play with time a little bit here to help us grasp what’s going on.

Awhile ago, I had the realization that if I spent 30 minutes per day doing something, I’d spend 1 week of that year doing it.

1 hour per day = 15 days per year

2 hours = 30 days (or another way to say this is 1 whole month)

Now, let’s give this some claws: the average millennial spends 5 hours per day on their phone. That means the average millennial spends 76 days per year on their phone. 2 full months a year, not like waking hours only, but 2 full months per year, a millennial somewhere stares at their phone.

An article just came out this week that says over 50% of US teens spend over 5 hours per day on social media (not just their phones) but on social media. Again, that’s 2 full months per year. That means if you have two teenagers in a room, every 5 years one of them will spend 1 entire year of those 5 years on social media.

Again, I don’t share this to say, we’re all wasting our time by how much screen time we engage in, use it better because God wants you to. The much bigger point is to say, because we are spending so much time on our screens, us and our kids included, we are being formed, or probably it’s more helpful to say deformed, by our digital devices in astronomical ways.

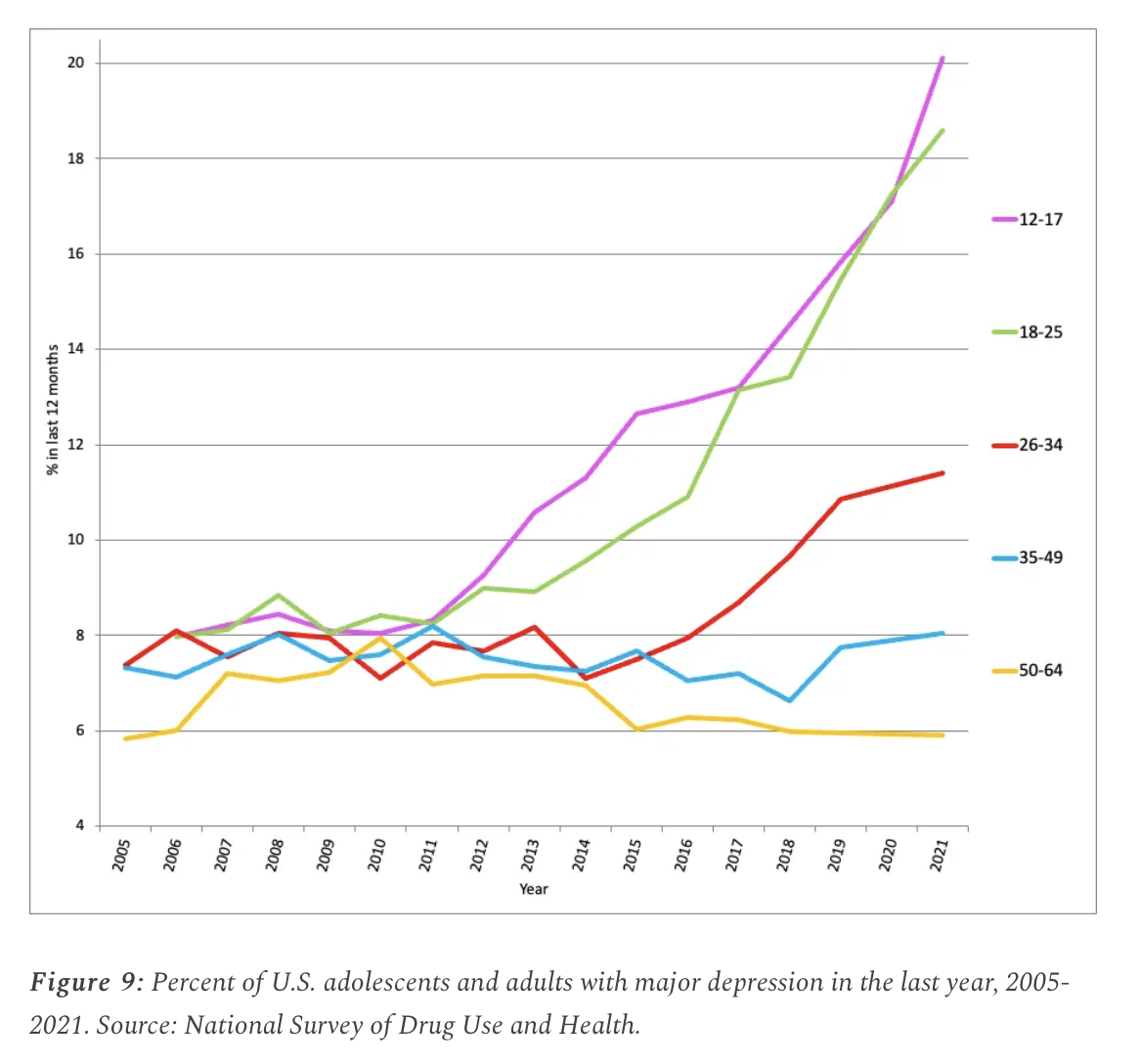

Much of the research that I’m showing comes from the work of Jean Twenge and Jonathan Haidt. They are two voices that starting around 2015 began voicing concerns about smartphone and social media use. Honestly, they have been fighting an extremely uphill battle until really the last year or two.

Jean Twenge’s hypothesis boiled down really simply is 2012 is the year that smartphone use toppled over to a majority of people owning one. For Twenge and Haidt that’s the dividing line. Both of them work in universities, so the precipitous decline in mental health was something they saw first hand amongst their students.

Here’s a little bit of a picture of what they started to see in the research.

Some pushed back on them and said “Well, maybe it’s because younger generations are more open to talking about mental health.”

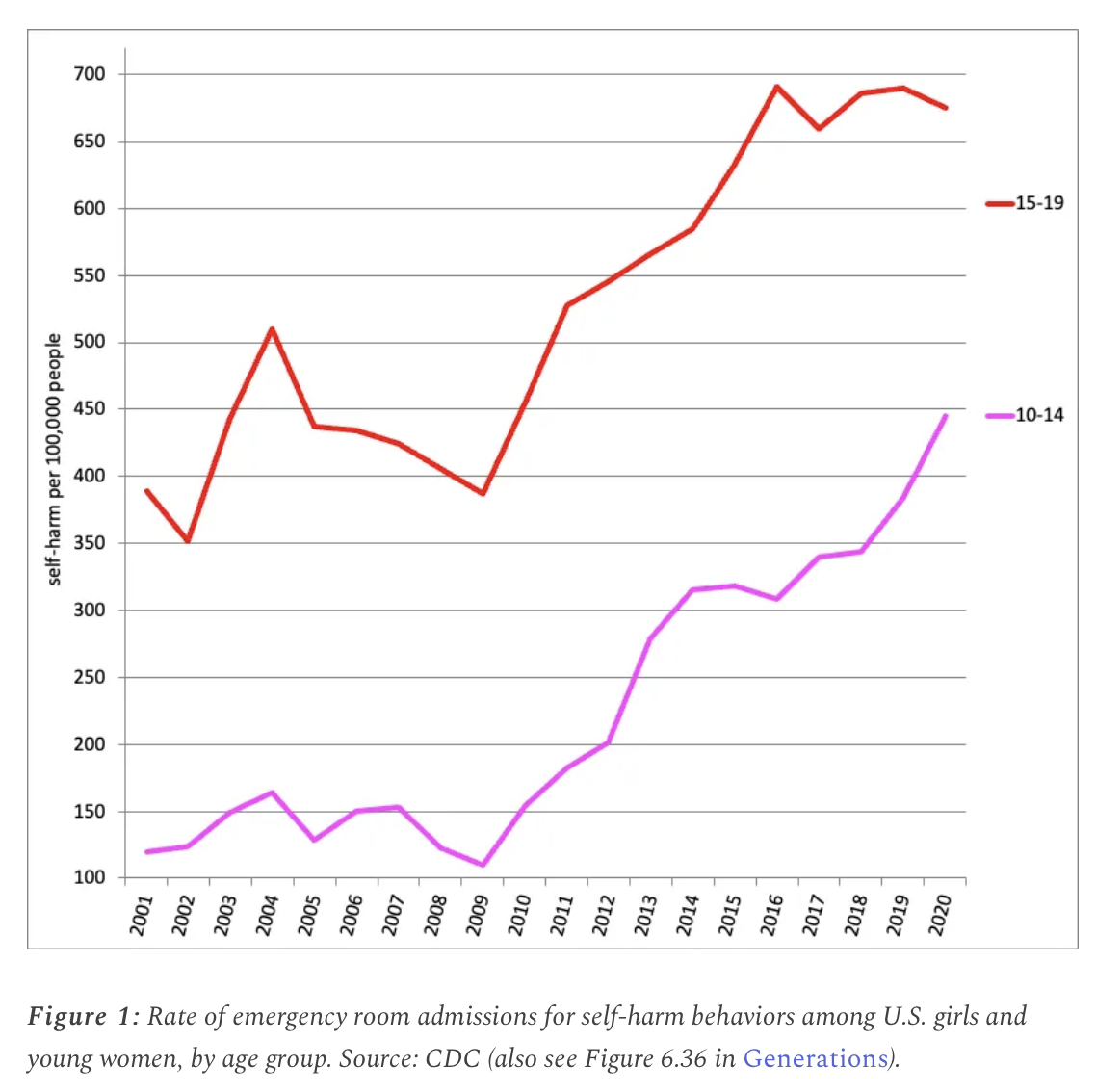

But Twenge and Haidt noted that it’s not just self-reporting, we see a rise in suicide attempts and hospitalizations.

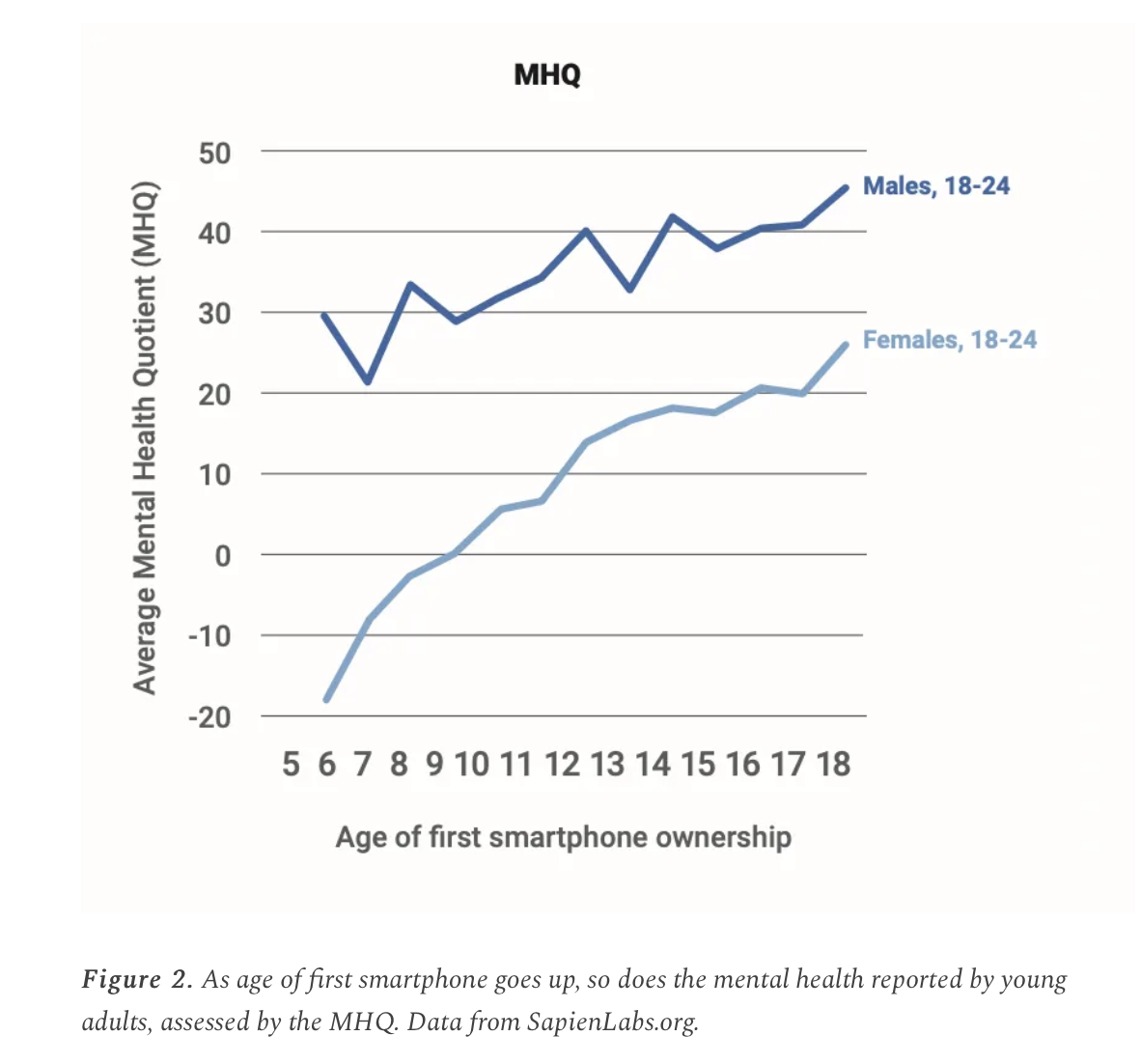

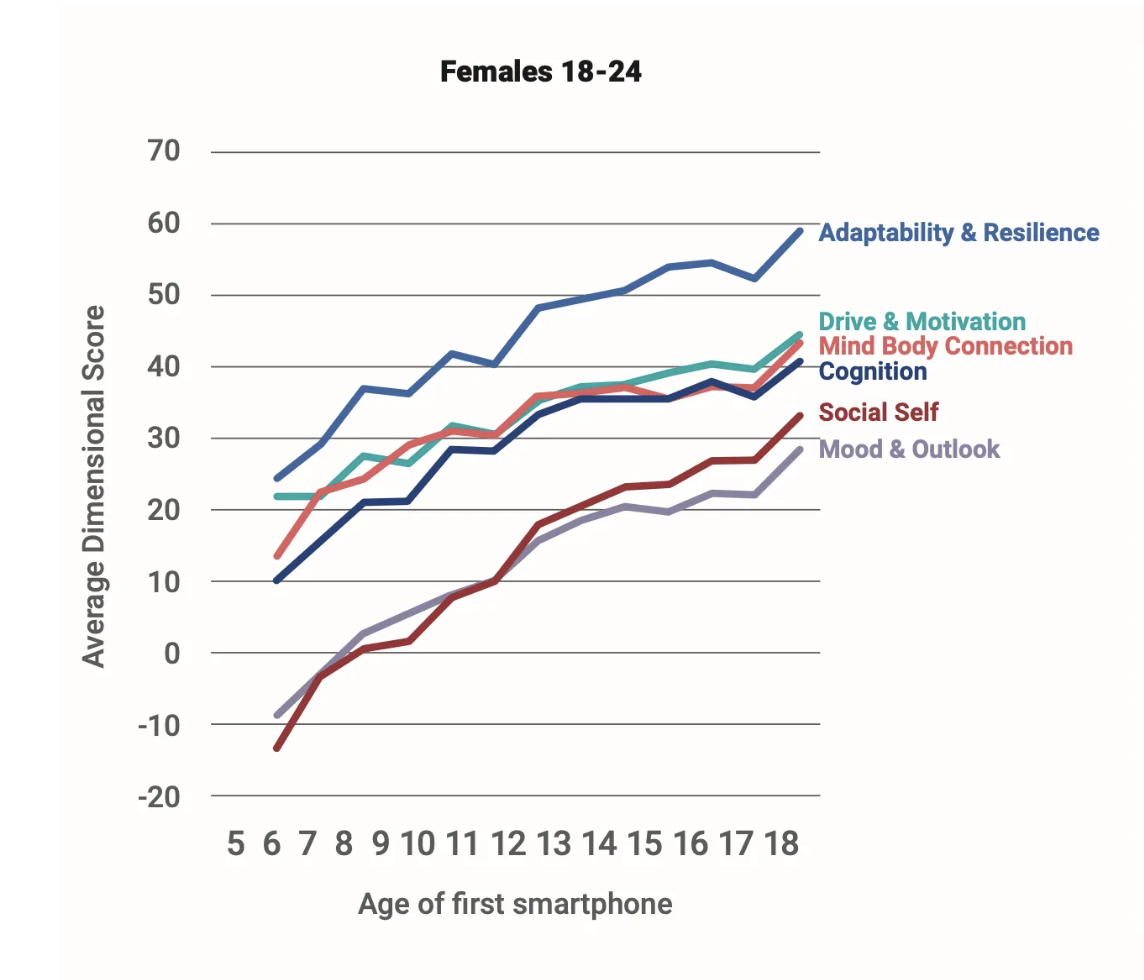

Zooming in a little bit, a study was published measuring the Mental Health Quotient of 30,000 teens and adolescents (from all over the world) looking at their Mental Health as a consequence of the age of their first smartphone (this study is world-wide, which is another reason Twenge & Haidt point towards smartphones and social media).

Some of the factors they’re examining are adaptability and resilience, drive and motivation, mind body connection, social self, mood and outlook. Here’s a look how these factors bear out for girls age 18–24.

Now, why is this so? Why are smartphones deforming our kids at such an alarming rate?

In his book 12 ways your phone is changing you, Reinke summarizes the effects that he sees smartphones having on us…

- Our phones amplify our addiction to distractions and thereby splinter our perception of our place in time.

- Our phones push us to evade the limits of embodiment and thereby cause us to treat one another harshly.

- Our phones feed our craving for immediate approval and promise to hedge against our fear of missing out.

- Our phones undermine key literary skills and, because of our lack of discipline, make it increasingly difficult for us to identify ultimate meaning.

- Our phones offer us a buffet of produced media and tempt us to indulge in visual vices.

- Our phones overtake and distort our identity and tempt us toward unhealthy isolation and loneliness.

Unfettered access to the internet via a device that is portable enough to be with you all the time, opens you up to worlds that were not even possible 10 years ago.

One of those worlds that is uniquely dangerous for undeveloped little plants, looking to grow deeper roots of identity into the soil is the world of social media.

Especially for young girls, social media is quite literally soul crushing.

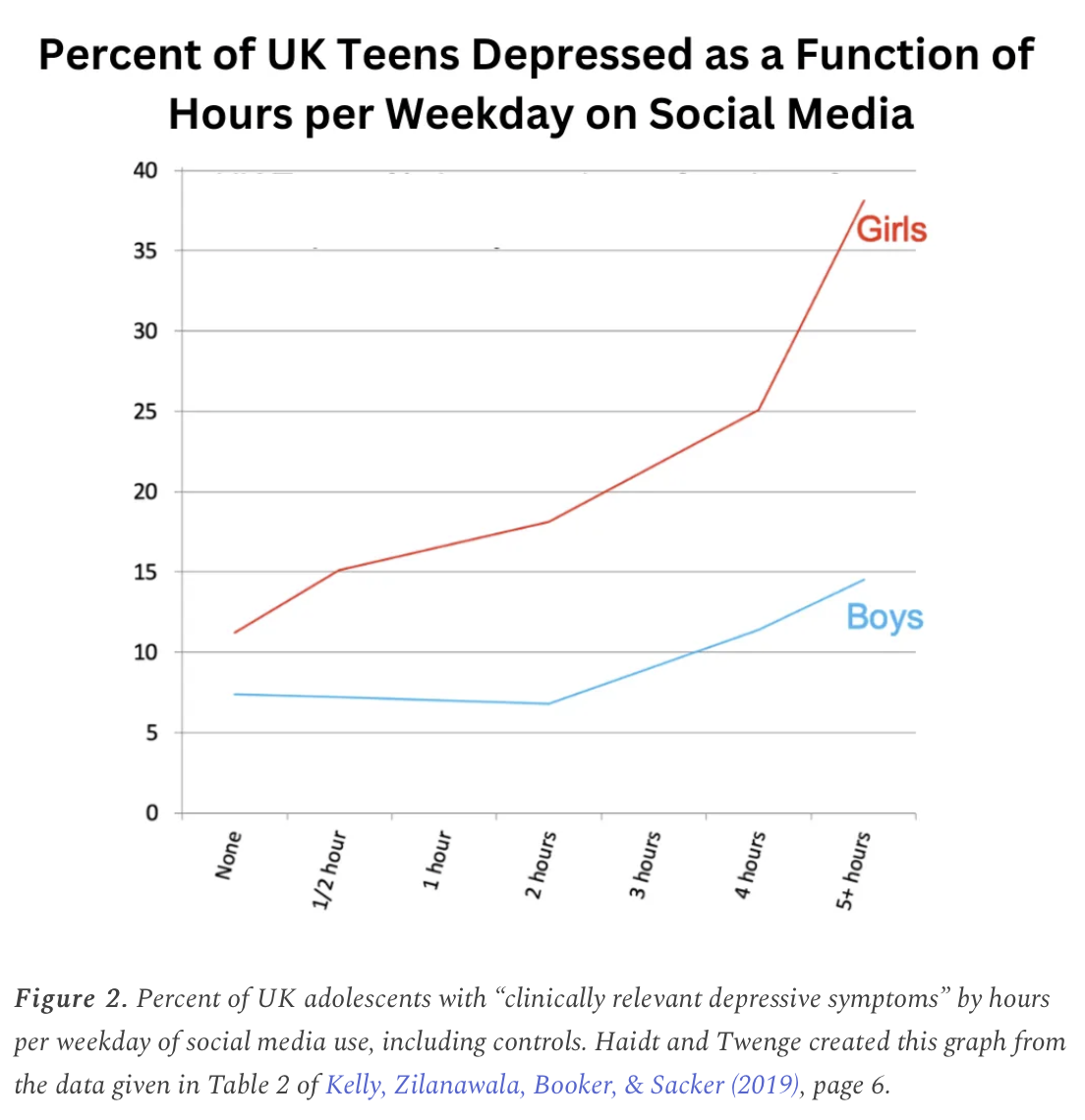

In a study on UK adolescents, you can see that there is a direct correlation between time spent on social media and mental health. For boys, the “dose response” starts at about 2 hours, which I wouldn’t take to mean that if boys have less than 2 hours of social media, they’ll not be formed or shaped in any way.

But still that leaves us asking why?

There’s a multiplicity of things at play here, but just a handful to consider:

- Loneliness

- Performativity

- Amplification of Harmful & Extreme Content

- Sleep Interference

- Replacement of Character-Forming Activities

Though the conclusion of Twenge, Haidt, and others is still debated by many, it does seem the tide is shifting in the conversation.

Just two days ago 33 states filed a lawsuits against Meta (formerly FB) for creating addictive features target at kids.

In May the surgeon general issued a warning against social media use for teenagers.

But, right now, the cultural default is that a kid will get a smartphone pretty much when they want, and that they’ll lie about their age and start allowing those TikTok Dopamine hits to start tapping on their brainstem.

The Vitality of Intentionality

A couple months ago I watched this early 2000’s movie, Idiocracy. In Luke Wilson participates in this military hibernation experiment gone wrong and finds himself waking up 500 years later in a dystopian future where the inundation of entertainment has made everybody dumb.

Somehow Luke Wilson gets arrested and as a part of his prison assessment takes an IQ test. In this Idiocracy, Luke Wilson tests as the smartest man in the whole world, and because of that, he works his way onto a place on the President’s cabinet to help solve the issues of the world as a way to get out of his prison sentence.

The largest problem that he thinks he can help with is the fact that the plants in the world will not grow.

Now, the movie on a whole is a critique of entertainment culture and what it can do, but I think connecting to our image of parenting as gardening, this clip and give us a little bit of a metaphor into thinking about technology.

You see in our technological age, I fear that parents (including Christians parents), much like the people of Idiocracy accepted Brawndo as the default source of hydration for all creation, we have simply accepted smartphone and social media use as the default position for all human beings.

I fear in a lot of ways we have been lulled to sleep, or maybe better to say seduced by the magic of a phone and an iPod combined, but now one that can deliver food to my door, show me stupid cat videos, and help me know what that person in Freshman biology is up to.

And I don’t want us to beat ourselves up about this, because it is a cultural and societal problem. However, I think we as Christians, above all else, should be able to step out of the cultural stream, to carefully examine it, and then ask: is [insert technology] forming my kids in ways that might help them flourish in Christ one day.

One of the founding fathers of media ecology once wrote, “…there is no inevitability as long as there is a willingness to contemplate what is happening…” (The Medium is the Massage, McLuhan & Fiore)

Another founding father, Neil Postman said…“We need to proceed with our eyes wide open, so that we may use technology rather than be used by it.” — Neil Postman, “Five Things We Need to Know About Technological Change”

And more importantly than my concern for me to be used by technology, I don’t want my kids to be.

I don’t want Mark Zuckerberg exploiting my children’s drive for connection so that he can have another billion dollars.

I don’t want ByteDance tapping on my kids biological circuitry for novelty, so that they can get TikTok Shop up off the ground.

I don’t want Sir Mix A Lot singing about “round things in my son’s face,” so Jeff Bezos can get a couple more cents on streaming revenues.

What I want more than anything for my kids is that is that they would experience the abundant life that Jesus promises in John 10:10.

What I want more than anything for my kids is that rather than experiencing the anxiety that is drummed up because of an always connected device is that they would experience the peace of Christ.

What I want more than anything for my kids is that rather than experiencing depression because so-and-so posted a picture of all their friends at a party that my kids didn’t get invited to, that they would still know that they are loved by God, who, if they’re in Christ, never excludes them, never rejects them, never embarrasses them, but loves them.

And I desire the same for your kids.

But to do so friends, it requires great intentionality. If you’ve ever walked across a flowing streams you know that it is exhausting; the same is true to walk across the stream of a technocratic culture.

But its one that is worth it and that our kids deserve.

Household Habits

Home is our school intimacy, where we first learn to be human. Its corners and nooks conceal the sweetness of solitude; its rooms frame our experience of relationship. Its shelter, stability, and security work to concentrate our unique inner sense of self, an identity that imbues our day dreams and night dreams forever. Its hiding places—closets, chests, drawers, locks, and keys—satisfy our need for mystery and independence. Doors—locked, closed, half shut, wide open—trigger our sense of wonder, safety, possibility, and adventure.

One habit that I have, that I imagine many of you have, and certainly many of your kids have, is engaging with multiple screens at one time.

- We may put on Black-ish on the TV, while we scroll the app formerly called Twitter.

- Or maybe we watch a YouTube video in the little Picture-in-Picture screen on the phone while we scroll Instagram on the same screen

- Or for our kids, maybe they play Fortnite on one screen, and watch TikTok videos while they wait for the room to fill to get started.

Expanding this out to all media, one (I’d say bad) habits I have, is putting on a game, or really any TV, and reading a book.

Why might I call this a bad habit?

If household habits form out children, and shapes who we are, I think it does at least 3 things:

First, it actually trains our children to not be present to one thing at a time.

Second, it trains our children to not embrace boredom.

Third, and maybe the most importantly to think about, I have a theory that it actually sops up more of our time when we do this. Why so?

I’ll call this the 2-Pizza Principle.

When you put one frozen pizza in the oven, it takes 22–24 minutes (if you’re making Red Barron Classic Crust). When you put 2 frozen pizzas in the oven, it doesn’t take 22–24 minutes; it takes closer to 30–35 minutes. I’m not a scientist, so I’m sure there’s some fancy formula or law of thermodynamics that explains this, but in simple terms, when there is more pizza in the oven, it takes longer to cook.

I think the same is true for screen time. When multiple screens are being used at one time, it takes longer for us to feel like we’ve had enough, like our brains are “cooked” in a sense. :P

I always get so pumped for the start of baseball season. It’s one part nostalgia, one part enjoyment and two parts hope of winter nearing its end. For those who don’t know, MLB has been working to speeding up the game by adding some pace-of-play improvements. But, you all know, baseball is a long and slow game (slow may be a pejorative for some of you).

Anyways, I was amped, ready for the season to start. So on opening day, I sat down to watch a game and was determined to actually practice this idea of one medium at a time. I made it about 3 innings before I was started thinking: “wow, baseball takes a long time.” I had made it 3 innings into he season and I was like, “Cool. I think I’m good. I’ll move on to something else.”

You see what happens when we use multiple screens at a time is we flit and float between them during our moments of boredom. Commercial comes on, I can watch a new batch of TikTok videos…book gets boring, I can close it for a few minutes and watch a couple at-bats before hopping back in.

Now, you may be saying, well if I spend 30 minutes on a show and 30 minutes on TikTok anyways, but I combine them, wouldn’t I spend less time on it? I would argue that it actually is the opposite effect.

I think when we nibble back and forth between screens, we experience a little bit of satiation at a time. But let’s say you do 5 minutes of TikTok and that adds 25% to your satiation tank, but then switch over to Fortnite for 10 minutes, your satiation tank goes down on TikTok, so that it takes longer to fill.

So, back to our 2-pizza principles, when you have multiple screens going at one time it actually takes longer for you to get to a place of “being cooked,” feeling like you’ve had your fill.

Now the danger of smartphones is that this becomes not just a multi-screen issue, it becomes a one-screen multi-app issue. And that is so scary and so dangerous.

We can flit and float between apps and have no idea how much time we’re spending on the device. We get a little bit of a fill with TikTok, then go over to Instagram, then over to Facebook, then Snapchat, then check the weather, by the time we’re done with those, our satiation tank has gone down, so we say, eh let me start the whole cycle again.

If our households engage in one screen (or medium) at a time, I think it would actually cut down on all screen time as a whole. But equally as important, it would help us to form children that are okay with being bored, and also are able to have sustained attention for longer than 7 seconds.

Phone Home

I think it is safe to say that your average user, especially your kids, is spending a majority of their phone use on non-utility type uses.

One of the goals of technology is to create a frictionless experience. The less friction there is, the more you’ll engage.

If I can illustrate this by thinking about a product that is the result of technological innovation: Cool Ranch Doritos. Here’s the deal: if there are Cool Ranch Doritos within arm’s reach, I will eat them. And I will eat a lot of them. That is especially true if I’m sitting on the couch in a heavy post up. The best thing is for Doritos to not be in near me. The even better thing that all health experts say is that they shouldn’t be in the house. If you don’t buy it, you can’t eat it. Pretty flawless logic.

The reality is that our willpower is actually so much incredibly lower than many of us think. It also is very much like a muscle. The more it’s used, the weaker it gets. So it’s much better to put ourselves in situations where we’re not solely dependent on will power.

Now What?

It’s better to let your choice flow from what you are for than what you are against…It’s better to imagine yourself working toward particular goods you would like to see materialize in your child’s life than simply proscribing the use of smartphones out of some justifiable murky apprehension. —Children and Technology, L.M. Sacasas

A recent Pew Research survey had almost 40% of teens report that “they spend too much time” on social media. That means there’s a 2/5 chance that your kids may welcome some familial structures around how everybody in the house engages with technology.

Resources

L.M. Sacasas, “Children and Technology”

L.M. Sacasas, “Care, Not Control”

Andy Crouch, Tech-Wise Family

Andy Crouch, The Life We’re Looking For

Cal Newport, Digital Minimalism

Jean Twenge & Jonathan Haidt, “Social Media & Mental Health” (Ongoing database of studies)

Nick Weyrens